Hear Me Out: Why Pulp Fiction Is A Great Christmas Movie

There is a way of talking about Christmas movies which treats Christmas as décor. Snow as shorthand. Lights as permission. A few chords of nostalgia and a moral lesson gently Hallmark wrapped so it won’t bruise anyone on the way down. Those films understand Christmas as atmosphere. Pulp Fiction understands Christmas, as many of us do, as ordeal.

This is why it endures. Not as a seasonal novelty, but as something closer to a ritual text. It is not interested in comfort. It is interested in interruption. In moments when the machinery of habit breaks down and a human being is forced. Briefly, unavoidably, to see themselves without the story they normally tell. That is Christmas, stripped of sentiment.

At its core, Christmas is an annual collision between time and meaning. The year closes in on itself. We pause not because life has slowed, but because the calendar insists. We gather not because it’s convenient, but because absence would say too much. We are asked quietly, insistently, whether we will remain who we have been, or whether we will take the risk of becoming someone else, even if only inwardly, even if no one applauds.

Pulp Fiction is structured entirely around that question.

Its famously fractured chronology is often treated as cleverness, but that misses the point. The film does not scramble time to show off. It scrambles time because moral awakening does not arrive in sequence. When people genuinely change, it isn’t progress. It’s re-interpretation. The past is still there, but rearranges itself. Events you once understood as fate suddenly look like warning shots. Choices you thought were small become decisive. Memory edits itself around a new center of gravity.

Christmas works the same way. Every year, we revisit the same rooms, the same streets, the same conversations. But we are not the same people standing in them. The repetition sharpens awareness. What once felt inevitable begins to look optional. The familiar becomes strangely interrogative.

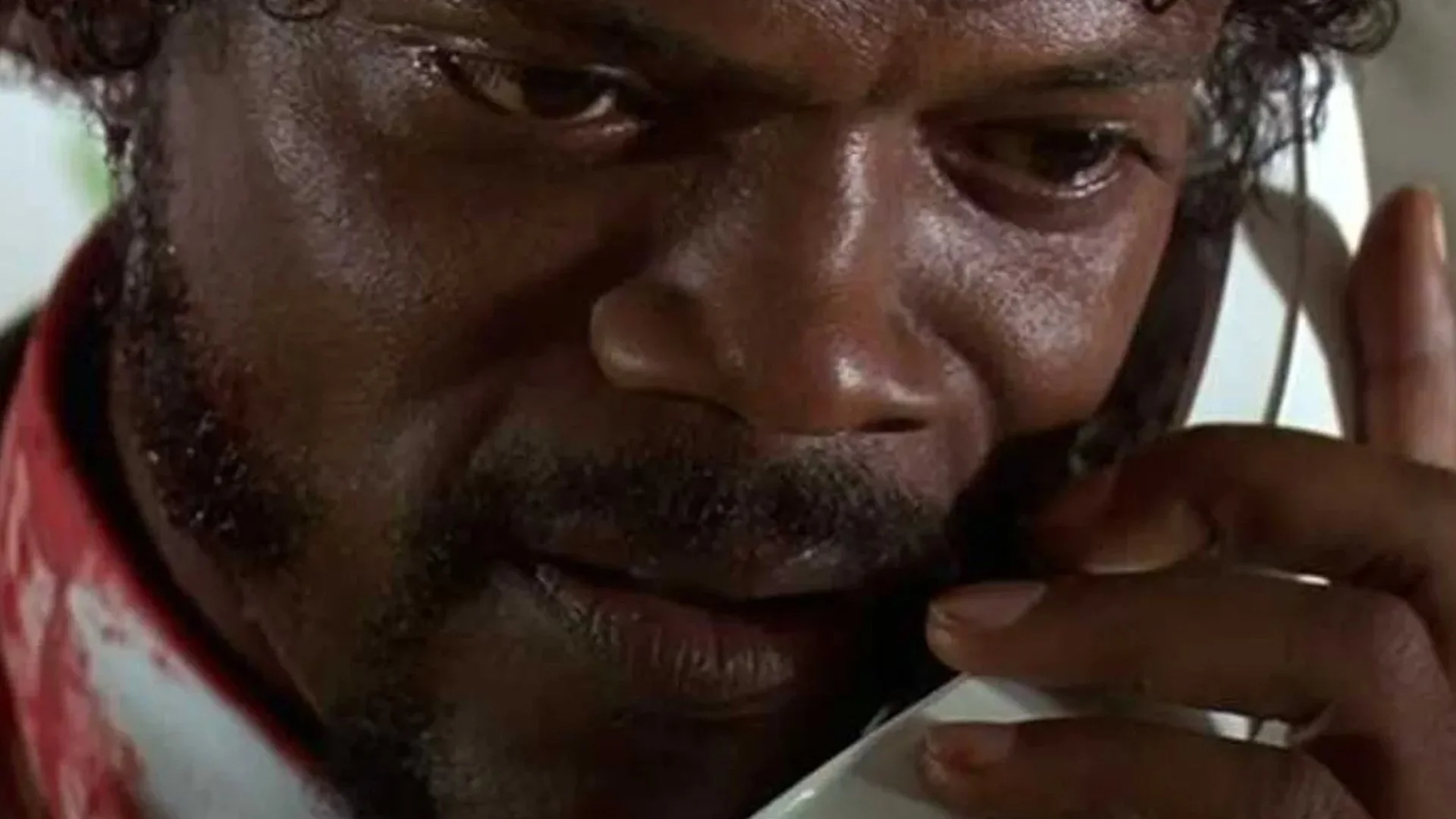

The first miracle in Pulp Fiction, the bullets which miss Jules and Vincent, is not simply cinematic luck. It is an interruption with metaphysical weight. Something impossible happens, and the universe briefly exposes the thinness of the script everyone thought they were following. What matters is that two men witness the same event and walk away with opposite interpretations.

Vincent treats it as an anomaly. An error in the system that can be safely ignored. Jules treats it as revelation. He does not become virtuous overnight. He does something much harder. He allows doubt to enter the identity he has been living inside. He admits that the words he has been reciting, the role he has been playing, might not mean what he thought they meant. Christmas does not convert people into saints. It destabilizes them. It introduces questions into routines that depend on certainty. It invites reflection at precisely the moment when reflection is most inconvenient.

Jules’ awakening is unsettling because it costs him coherence. The story he tells about himself no longer holds. And once that happens, he has only two options. Rebuild the story on humbler terms, or double down on violence to silence the question. That choice, whether to respond to existential discomfort with domination or restraint, is the quiet moral axis of the film. And it is a deeply Christmas axis.

The film’s violence is often mistaken for nihilism, but it functions more like exposure. Violence strips away pretense. It reveals who people are when scripts fail. Christmas does something similar, albeit with fewer guns. It places us under emotional pressure and removes the usual exits. Old roles resurface. Old resentments speak. Old fears flare. It becomes harder to hide behind politeness.

Consider the diner scene, which is the closest thing the film has to a nativity tableau. A public space. Ordinary people. Early morning light. A crime in progress which suddenly turns inward. The setting is not sacred, but it becomes so because of what happens there. Jules does not resolve the situation by force, though he has every reason and ability to do so. Instead, he reframes it. He treats the moment not as an opportunity to assert power, but as a test he did not know he was taking.

This is crucial. Redemption in Pulp Fiction does not arrive through confession or punishment. It arrives through restraint. Through the refusal to repeat a familiar pattern even when repeating it would be easier, safer, and socially legible. This is why the diner scene feels quietly shocking. It violates our expectations not of crime, but of masculinity. Jules steps away from the performance of control. He allows uncertainty to stand. He chooses not to define himself through dominance.

That choice is profoundly unspectacular. There is no swelling music. No public recognition. The world does not rearrange itself around his decision. He simply walks out different than he walked in. That is what real moral change looks like.

Christmas movies often promise transformation without residue. Pulp Fiction insists that change leaves marks. Jules loses something by choosing a different path. His certainty, his role, his sense of inevitability. What he gains is not clarity, but orientation. A willingness to walk without knowing exactly where the road leads.

The film is filled with characters who refuse this discomfort. Vincent clings to routine and is undone by it. Mia survives an overdose but does not fundamentally change. Butch escapes, but only after confronting a version of himself he would rather not acknowledge. Each character is offered a moment of interruption. Only some accept it. This mirrors the real experience of Christmas more closely than any feel-good montage. The holiday does not redeem everyone. It reveals who is ready and who is not. It exposes fault lines that already existed. It does not heal by force. It clarifies by pressure.

Even the film’s fixation on objects. The briefcase, the watch, the gun left on the counter, function symbolically. These items carry disproportionate weight because they stand in for meaning itself. People cling to them because they promise continuity. They say this mattered before, therefore it must still matter now. Christmas is saturated with such objects. Ornaments, recipes, heirlooms, songs. We invest them with meaning not because they are sacred, but because they anchor us against time’s erosion. The danger, as Pulp Fiction shows, is mistaking the object for the value it once represented. When that happens, ritual becomes fetish, and tradition becomes inertia.

The film’s final grace is that it refuses to tell us what comes next. Jules’ future is unwritten. He is not rewarded with a better life on screen. The point is not outcome. The point is posture. He has learned how to stand differently in the world. This is the most honest Christmas ending imaginable.

Because Christmas does not solve your life. It offers you a moment, a pause in the noise, where you might see yourself clearly enough to choose differently next time. The power lies not in the holiday itself, but in what you carry forward after it passes. Pulp Fiction earns its place as the greatest Christmas movie because it understands this truth without ever naming it. It treats grace as interruption, redemption as restraint, and time as something that can be stepped out of. If you are brave enough to notice. It does not promise comfort. It offers recognition.

And in a world addicted to momentum, that recognition, the moment when the bullets miss, the story stalls, and you realize you are not trapped inside who you have been, is the most Christmas gift of all.

Latest Articles