Remembrance As Resistance: I’m Still Here

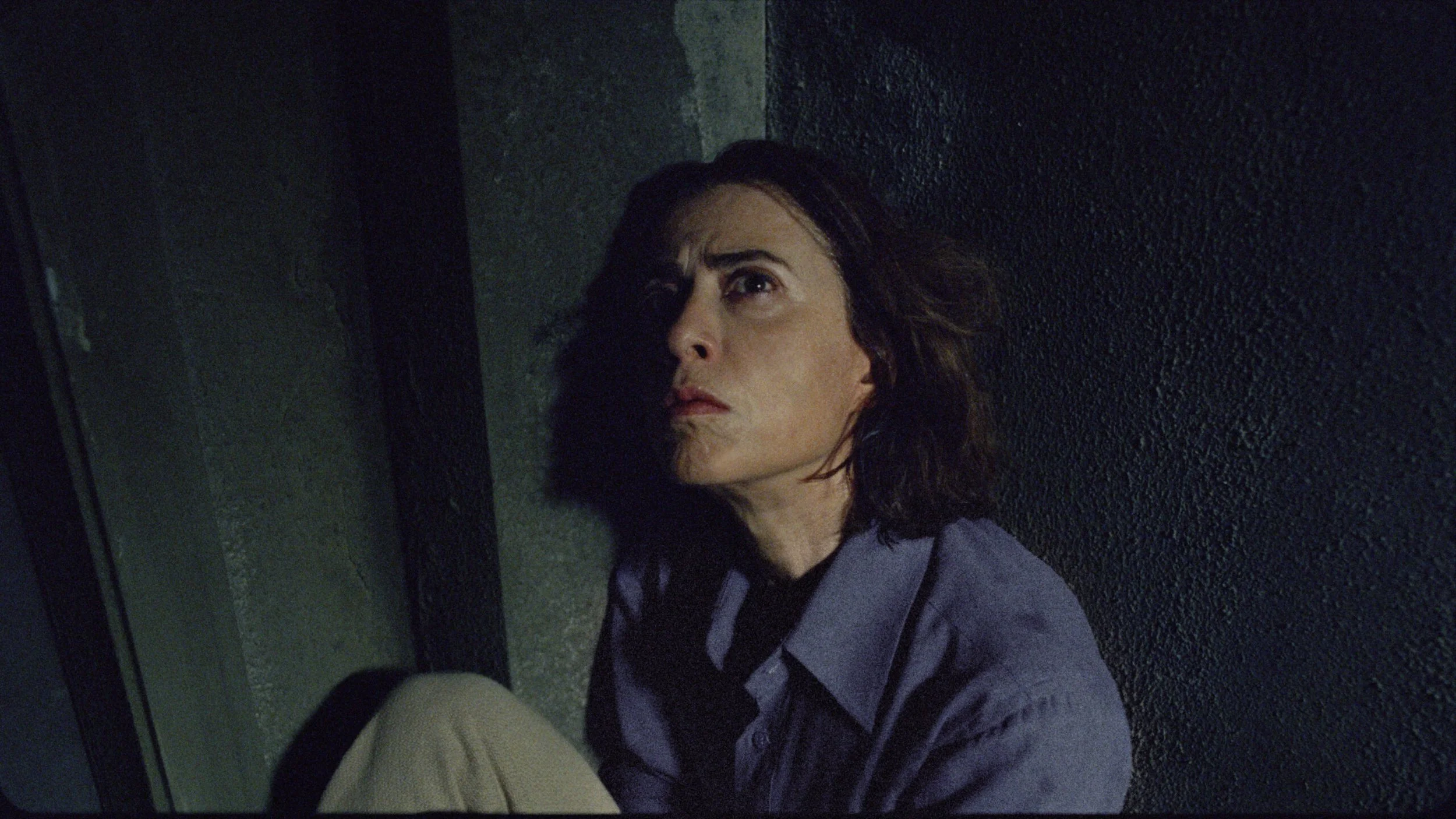

There’s a particular ache that comes from returning to a home that no longer remembers you. Rooms look the same, the air holds a faint echo of something once known, but the life that animated the space has long since moved on. Been taken. In I’m Still Here, a quietly devastating Brazilian film, this ache forms the emotional spine of a story that is less about what happens and more about what is erased. It is a film about absence. How it accumulates, how it settles into the corners of the house, and how it must be combated if we are to retain our humanity.

Set against the shadowed backdrop of Brazil’s military dictatorship, the film follows a family fractured by state violence. The father, a political prisoner, is brutalized through an institutional system of torture designed not only to extract information, but to obliterate memory. He is held without charge, moved without record, and subjected to a form of violence that is as psychological as it is physical. But what makes I’m Still Here linger long after the credits roll is not its depiction of political horror, though that is visceral, but its nuanced meditation on memory, and the silent war waged against it.

The film is obsessed with the artifacts of personal history: photographs, cassette tapes, furniture, wallpaper, old television broadcasts. These are not mere set dressings; they are battlegrounds. Each object in the frame is freighted with significance. A cue to memory, a conduit for grief. And when the father is disappeared, the absence is not just felt in the family’s daily life, but in their sensory landscape. The music he loved grows quiet. The television, once a source of family entertainment, begins to speak in the voice of the state. The home movies sit unwatched, as if doing so would rupture what little peace remains.

Technology in I’m Still Here is shown in its dual role: as a vessel of memory and a vector of manipulation. The cassette player, once used to share music or preserve moments, becomes a relic of connection. A shrine. But the television, with its flickering propaganda and shifting news cycles, is something else entirely: a mouthpiece for forgetting. It broadcasts the government’s truth, which is not the truth at all. And so, inside the walls of the home, the family must navigate competing realities. What they remember, and what they are told to remember.

The father’s torture is, in a chilling sense, an act of enforced amnesia. It is not just the body that the regime breaks, but the timeline. He is disoriented, disconnected, removed from any frame of continuity. The authorities don’t just want him to confess, they want him to forget. Forget who he is, forget who he loves, forget what he stood for. Torture becomes a form of historical sabotage. And for the viewer, this is not abstract. It is intimate, harrowing. We see the toll it takes not only on the victim, but on those trying to hold his memory intact in his absence.

The mother’s role is particularly moving in this regard. She becomes the keeper of the flame. Guardian of photographs, of stories, of ritual. In one quietly powerful scene, she prepares the father’s favorite meal even though she knows he won’t return that night. Memory, for her, becomes an act of resistance. Cooking, dusting, playing a song, all become small rebellions against the silence imposed by the state.

The child, too, moves through the film in a state of impressionable wonder and confusion. The past is not something he fully understands; it is something he feels. For children, memories are not assembled rationally. They are formed through sensation, sound, and repetition. And as he navigates the strange space between presence and absence, his understanding of his father becomes shaped by the environment itself. His voice on a tape, his smile in a photograph, the hushed tones of adult conversation. These memories will eventually harden into nostalgia. Filtered through emotion, distorted by time, but they will remain. The film understands this perfectly. It honors the quiet violence of childhood under dictatorship: the things not said, the things said too late.

Perhaps the most haunting motif in I’m Still Here is the house itself. It is not merely a location, it is a character, a container of the past. The film lingers on doorways, hallways, kitchen tiles. Places that once held life, now hollowed out. The home becomes a kind of museum, but one that is still alive, still waiting. Even when the family is forced to relocate, the previous house holds their memories like a sealed room. This idea, that our former homes continue to remember us even after we’ve left, is one of the film’s most quietly devastating insights. We do not simply move on; we scatter ourselves across time and place.

In this way, I’m Still Here aligns itself with a broader, more painful truth: that memory is not static, and it is not safe. It must be maintained, tended, fought for. Because the state, in its quest for control, understands something very clearly: to dominate the future, one must rewrite the past. The erasure of records, the manipulation of media, the distortion of facts. These are not side effects of authoritarianism. They are its primary tools.

There is a moral core to this film that is inescapable. It asks us to consider what it means to remember responsibly. Not simply to be nostalgic, but to be vigilant. To resist the simplification of history into soundbites. To honor the difference between recorded history and lived experience. The regime in I’m Still Here would have the world believe that its violence never occurred, or that it was necessary, or that it has been forgiven. The film itself stands in defiance of that notion. It is a monument to the people who do not forget.

In the final scenes, as the family attempts to live again in the aftermath of rupture, there is no dramatic catharsis. There is only continuity. A quiet insistence that life persists, that memory endures. A child sings a song his father once loved. A photograph is moved to a different shelf. The house breathes again, gently.

I’m Still Here is not a loud film. It is a haunted one. And like memory itself, it requires attention, patience, and a willingness to feel what is no longer visible. In doing so, it offers something rare and necessary: a reminder that remembering is not a passive act. It is moral. It is political. And it is the only defense we have against the machinery of forgetting.

Disclosure: This article is an experiment created with generative research tools trained on my previous archive of writing. It relies upon a number of online sources for its original hypothesis as well as the assembly of narrative conclusion. It is an experiment in crafting a detailed set of instructions sufficient to prompt an LLM to generate a topic of esoteric interest based on my own interest in film criticism, perform a deep analysis upon these topics, and assemble them into a coherent, informed set of thoughts. I find the results a fascinating means of surfacing new and interesting threads of curiosity. I hope you do too.