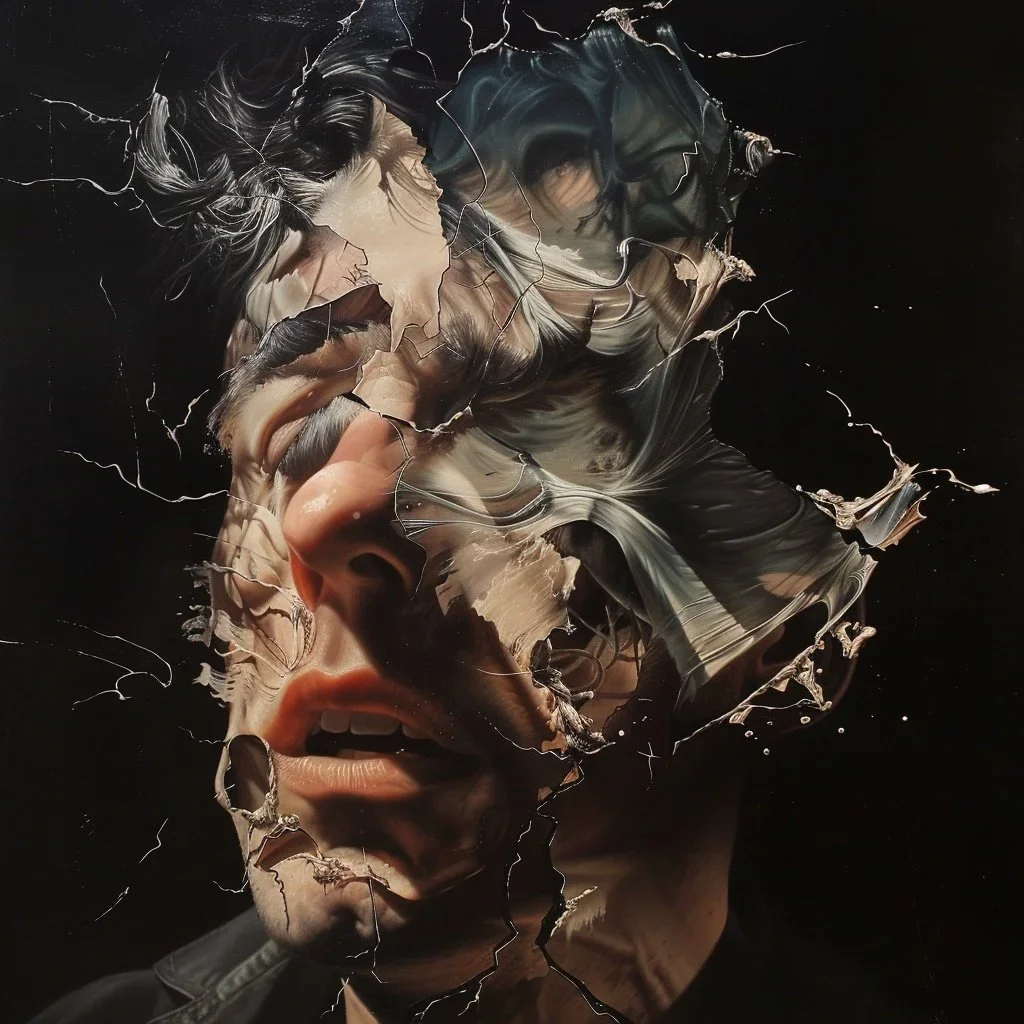

If Product’s On Fire, Then Everyone’s On Fire

There’s a phrase I come back to again and again with my teams.

If Product is on fire, then everyone is on fire.

What I mean is simple. Emotional states don’t stay contained. They radiate outward. Engineering feel it. Design feel it. Project management feel it. Stakeholders definitely feel it. In other words, the product manager’s emotional state is part of the product surface area.

We talk a lot in product management about strategy, roadmaps, KPIs, and influence without authority. We talk less about what it means to be the person who walks into a room that’s already at a rolling boil and manages, somehow, to lower the temperature. Not by pretending things are fine, but by being calm enough that other people can think clearly.

Calm is not the absence of urgency. Calm is the container for it.

Positive psychology has a useful frame for this. Barbara Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory suggests that positive emotions literally widen our field of view. They broaden our thought to action repertoire so we can see more options and build lasting resources. Cognitive, social, and emotional.

By contrast, negative emotions narrow. They’re great if you need to run from a tiger. But terrible if you’re trying to untangle a gnarly dependency chain or negotiate scope without torching trust.

When a product manager arrives in a stand-up radiating the sky is falling, everyone else’s world narrows with them. Ideas shrink. Options collapse. People cling to the safest, most defensive behaviors. Blame. Avoidance. Silence.

When a product manager is steady, not checked out, not fake-positive, but truly grounded, the team’s psychological aperture widens. Colleagues are empowered and enabled to stay curious and humble under pressure. They become more able to hold multiple possibilities at once. They can disagree without escalation. And as product manager, your nervous system becomes a shared, renewable resource, but you’re also the circuit breaker for others.

I’ve often framed product work as stewardship more than heroics. The campsite rule of leaving teams and products better than you found them, the fog-as-feature of working inside ambiguity, the so let’s do this move which gently lands a swirling conversation into a concrete next step. This is firmly within the same lineage.

Being calm and collected for others is not a nice-to-have personality trait. It’s part of the infrastructure of the work, and it’s essential for both users and the needs of the business. It’s the emotional equivalent of observability or uptime. When it fails, everything else degrades.

In practical terms, this means:

You are the circuit breaker for panic.

When an executive escalates in all caps, when a data issue hits the homepage, when a dependency slips two sprints, your first job isn’t to solve the problem. Your first job is to break the circuit between this is bad and we are all bad at our jobs. You slow the rush to self-blame and re-center on what happened and what we do next.

You are the translator, not the amplifier.

Stakeholders can often arrive with fear, urgency, sometimes anger. Engineers might arrive with complexity, constraints, sometimes frustration. If you simply reflect and mirror those emotions back and forth, you only amplify noise. If you translate what I hear you worried about is X, and what the team is saying is Y, here’s the overlap, you can create signal.

You are the stable reference point.

In a high-ambiguity culture, the product roadmap will move, org charts will redraw themselves, and priorities will reshuffle. Your demeanor as the product manager is one of the few constants people directly experience. Over time, that becomes part of your brand. No matter how bad it gets, when we go to them, the room gets clearer, not hotter.

So, calm is not a mood board. It’s a set of behaviors other people can reliably experience, and dependably rely upon.

More tactical advice, with some real examples I’ve heard :

You narrate reality without drama.

We missed the SLA by six minutes. Here’s where it broke, here’s who is looking at it, here’s what we’re going to learn from it. Notice the lack of adjectives. Short, crisp sentences will be your friend here. You’re specific, you’re honest, but you’re not catastrophizing.

You slow down the moment that wants to speed up.

Before we jump to solutions, let’s make sure we agree on the problem in one sentence. When everyone else is in fight-or-flight, you introduce one beat of reflection. That beat is where better decisions get in. I saw a product manager do this with a group of stakeholders who simply could not come to a point of agreement about a solution. But what they could all agree on was what that one sentence was. Starting from a place of agreement is more productive than trying to solutionize large-scale disagreement.

You respond, even when you don’t have the answer.

Nothing spikes anxiety like silence from the person who’s supposed to be steering. A calm product manager doesn’t disappear into Slack DMs when things go wrong. They know that wartime comms are everything, and show up and say, I don’t know yet. Here’s what I’m doing in the next hour. Here’s when you’ll hear from me.

You separate urgency from hostility.

I can tell this is really important to you, and I want to be sensitive that. Let’s focus it on what we can change this week. You don’t mirror someone’s email tone back at them. You metabolize it and give the room something more workable.

You protect thinking time in the middle of chaos.

Calm product managers quietly guard moments where engineers can actually…think. They push back on just jump on a call pile-ons when a focused 30 minutes of debugging would do more than 10 people on mute watching a screen share. They know when to be quiet.

These aren’t grand gestures. They’re small, repeatable choices. Over time they compound into reputation. People start to bring you their real problems earlier because they trust you won’t set them on fire for doing so.

Of course, all of this assumes one thing: that you’re not actually on fire inside yourself.

In positive psychology terms, you can’t broaden and build for others if you’re permanently narrowed and depleted yourself. Being calm for the room means you need some kind of practice that keeps you resourced.

A few that map cleanly into product life:

Pre-mortems on your own stress.

Ahead of a big launch, write down what kinds of things, if they go wrong, are most likely to rattle me? Maybe it’s executive scrutiny, maybe it’s public metrics, maybe it’s fear of letting the team down. Noticing your patterns ahead of time makes it easier to recognize them in the moment and not confuse them with reality.

A simple ‘worst day’ reframing.

When things truly do go sideways, it helps to remember that your worst professional days are still just that, part of your past, not your future. You are allowed to learn from them, not live in them. This lens keeps painful incidents as data points, not permanent verdicts on your existence.

Tight, honest communication hygiene.

When you’re overwhelmed, the temptation is to vanish into work. Instead, practice sending three-line updates. What happened. What you’re doing. When they’ll hear more. This is a gift to others, but also a regulation tool for you: you move from amorphous dread to concrete action.

Boundary-shaped ambition.

Great product managers are often wired for responsibility. Everything feels like it ultimately rolls up to you. Calm leadership requires the opposite move. Surgically deciding what is yours to carry and what belongs somewhere else. Ops, security, another team. You’re not calming the room if all you’re doing is quietly becoming its emotional landfill.

Deliberate joy and perspective.

It sounds indulgent. It isn’t. Small experiences of joy, gratitude, or pride actually expand your thinking and resilience over time. That might mean keeping a quick three good things from this sprint note. Or pausing to celebrate a resolved bug that used to keep you up at night. You’re literally building the emotional reserves you will draw on in the next fire.

If Product is on fire, then everyone is on fire isn’t just a warning. It’s a design constraint.

We already accept that uptime targets, error budgets, and reliability are non-negotiable aspects of a product’s quality. Emotional reliability is exactly the same. Your ability to bring calm, clarity, and care into high-stress situations is not a side quest. It is part of the product.

Because in the end, this work is brutally simple:

When everything goes wrong, does the team do their best thinking or their worst?

After the fire drill, do people trust each other more or less?

When your name pops up in a notification, do people brace… or breathe?

As a product manager, you don’t always get to choose what happens. But you do get to choose whether you become another accelerant, or the person who shows up with water, a plan, and the kind of steady presence that lets everyone else remember what they’re capable of.

There will always be fires. Calm is how you make sure they don’t burn your product, or your people, to the ground.

Latest Articles