It’s You I Like: Why Mr. Rogers Would Have Been A Great Product Manager

Some days I think the best product management handbook we never got is hidden inside a red cardigan.

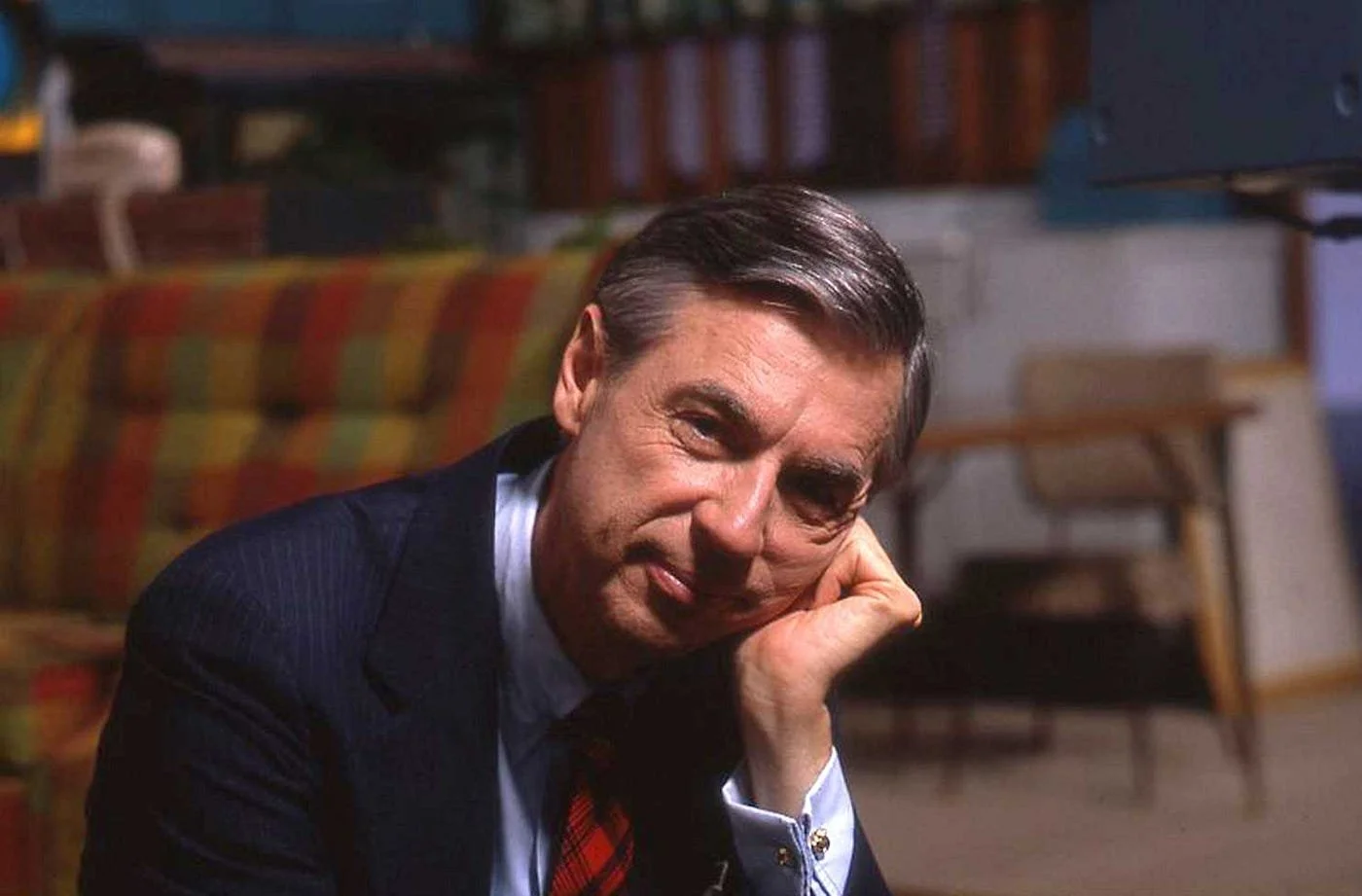

Strip away the puppets, the theme song, and the miniature trolley, and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood is one of the most successful products of all time. Decades of daily episodes, cross-platform distribution, inter-generational user loyalty which lasts a lifetime, and a brand moat built almost entirely on kindness. But put aside all the corporate jargon and underneath all the gentle small talk was a ferociously clear product philosophy.

Fred Rogers would have been an extraordinary product manager.

Not because he could run a sprint planning session (though I bet he’d rigorously color-code his Post-its), but because his curiosity for the world was built around optimism, creativity, and, above all, kindness. The things we keep pretending are soft skills in product work were the only skills he ever treated as non-negotiable.

Rogers once said he felt “deep and simple is far more essential than shallow and complex.” That’s always a good place to start with any new product.

He never chased complexity for its own sake. A typical episode revolves around a haircut, a new sibling, a scary sound at night. Deliberately and consistently minimal. One human, one camera, long unbroken shots, a tiny model trolley. But the emotional depth is enormous.

Translate that into product management. He’d ask “What is this really for?” until the room got quiet. He’d trade cleverness for clarity every single time.

“Deep and simple” gets at how we decide not to ship eight disjointed features, and instead ship one coherent path which genuinely changes our user’s day.

Alas, most teams are rewarded for shallow and complex. Glossy decks, clever frameworks, the optics of dashboards which look impressive but explain very little. Rogers would be the one who keeps editing the slide down to the insightful sentence nobody can quite hide from.

One of Mister Rogers’ most quoted lines is “Anything that’s human is mentionable, and anything that is mentionable can be more manageable.”

That’s not just good parenting advice. It’s the blueprint for high-trust culture. Product managers live at the intersection of such uncomfortable feelings. Fear of being wrong, fear of missing the quarter’s KPIs, fear of shipping late, fear of shipping junk. Fear, fear, fear. In too many organizations, nobody is allowed to say any of that out loud. The result is performative confidence, sandbagged stakeholder conversations and roadmaps, and a lot of hidden risk.

Rogers built an entire universe whose first rule was if you can name it, we can face it together. Anger, jealousy, grief, shame. The “inner drama of childhood” he talked about in his 1969 Senate testimony when he defended funding for public broadcasting.

Great product managers do something similar in their teams. In a planning review, they say things like “It sounds like we’re afraid this dependency will slip and nobody wants to admit it. Let’s name that and plan for it.” In a retro they say “It’s human to feel embarrassed about this outage. Let’s talk through it so it becomes manageable, not paralyzing.” Or in a design review, “If this feels confusing to us, it will be confusing to our users.”

Rogers would be the PM who treats every hard conversation as a chance to make complexity smaller simply by making it speakable.

Product management is also mostly the art of changing minds you don’t control. I hear this all the time in my teams.

Fred Rogers never had formal authority over the U.S. Senate. Yet in 1969 he walked into a skeptical hearing, where funding for public broadcasting was about to be cut in half, and in six soft-spoken minutes, completely changed the outcome.

He didn’t win by wielding data as a weapon. He described what his “product” did for its users. Helping children name their feelings, feel safe, and grow up less afraid. He even recited lyrics from one of his songs to show how carefully he spoke to children about anger. By the end, Senator Pastore, who had been openly impatient, said simply, “I think it’s wonderful. Looks like you just earned the $20 million.”

That’s true influencing without authority.

Or consider the famous pool scene with Officer Clemmons. Also in 1969, when integrated swimming pools were still controversial, Rogers invited François Clemmons, a Black police officer on the show, to soak his feet in a small wading pool with him and then share his towel. It was a quiet, powerful, visual rebuttal of segregation, broadcast into living rooms across America.

No speech. Just an experience designed to change what children assumed was normal.

In a company, that’s the PM who doesn’t win the prioritization debate by being the loudest voice, but by telling the clearest story about the user and the stakes. They designs small rituals. Moments where we decide how we kick off a meeting, how we share credit, how we talk about failure, which quietly shift culture over time. And they use the product itself as an argument for better values. Accessibility which isn’t bolted on, inclusive defaults, features that assume a wide, human range of users.

Rogers’ superpower was that he never forgot he was modeling behavior. Great product managers do the same.

Near the end of his life, in a message recorded for the now-grown children who’d watched him, Rogers said: “I would like to tell you what I often told you when you were much younger. I like you just the way you are.” He said some version of that for decades. “You’ve made this day a special day, by just your being you.”

Most products quietly tell users You’ll be good enough once you hit this streak, this metric, this status. Rogers inverted that. You’re already enough. The product exists to support who you are, not fix you.

He wouldn’t dismiss metrics. This is someone who obsessively measured emotional outcomes in children. But he would refuse to optimize by shaming his users into engagement. No dark patterns. No anxiety-driven nudges. No “you’re falling behind, better catch up.”

Instead, he’d ask does this feature help people feel more like themselves, or less? Are we treating our users as problems to solve or as neighbors to serve? Would I feel comfortable explaining this retention tactic to a five-year-old?

And he’d extend that same radical acceptance to the team. The junior engineer who’s scared they’re not senior enough yet. The designer who’s sure they’re “too soft” for tough negotiations. The PM who’s burned out but afraid to admit it. Rogers would be the one saying you are already worthy of being here, and from that safety, growth can actually happen.

Rogers often told the story of his mother’s advice when scary things appeared on the news: “Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.”

Optimism, for him, was never denial. It was selective attention as a survival skill.

Product managers live inside a rolling news cycle of their own. Production incidents, missed targets, reorgs, strategic u-turns. It’s easy to become the confident cynic in the room. The one who’s always ready with a “this will never work” quip. A posture which feels smart to those who say it, but it kills momentum.

Rogers’ version of optimism is much more demanding. It asks, in this outage, who are the helpers? How do we empower them and learn from them? In this failed experiment, what did we just buy with this data? In this reorg, what new paths opened up that weren’t there before?

He didn’t ignore pain or pretend everything was fine. He acknowledged fear and then gently turned attention toward the people who were making things better. That is exactly what good product leaders do when they help teams metabolize failure into learning instead of shame.

But if there’s one case study every PM should watch, it’s the visit from Jeff Erlanger, a then ten-year-old boy who used an electric wheelchair. Rogers had met Jeff years earlier and, when he wrote a script involving a wheelchair, he insisted they bring Jeff and his family in from Wisconsin rather than casting someone local.

The segment is unscripted. Rogers kneels beside Jeff, asks simple, honest questions about his disability, lets Jeff explain surgery and paralysis in his own words, and then they sing “It’s You I Like” together. It’s a wonderful, tender piece of television. You can watch Rogers continually hand control of the conversation back to Jeff, making space for his experience to be the center.

From a product perspective, this is an absolute masterclass in kindness, and inside it bears some powerful tactics. It invites someone in with lived experience, without making assumptions from a distance. And uses a platform so kids with disabilities see themselves on screen as whole, joyful humans, not side characters. But more than anything, it’s a demonstration that kindness is not a layer of UI polish you sprinkle at the end. It is the product. It’s what we build and how we build it.

Rogers wasn’t trying to cynically “drive engagement with disabled users.” He was simply trying to be a good neighbor. And in doing so, he built intergenerational trust which has lasted decades, to the point where PBS is still creating characters inspired by Jeff’s story to help disabled kids feel seen.

If Fred Rogers sat in on your next roadmap review, I think he’d quietly look around the room and ask who here feels safe enough to tell the truth? Where is this product making people feel more human, not less? What would it look like to make a deep and simple thing, instead of a shallow and complex one? How are you treating your colleagues as neighbors, not just resources? When the hard news hits, do you know where to look for the helpers. And are you one of them?

Kindness, in his world, was not niceness. It was an operational discipline. It showed up in how he prepared, how he listened, how he argued for funding, how he designed scenes which quietly pushed back on racism and exclusion.

Product managers spend a lot of time talking about influence, impact, and execution. Mr. Rogers reminds us that the sharpest tools we have for all three are often the ones we’re most uncomfortable to name. Attention, patience, curiosity, hope, and a stubborn commitment to caring for other people.

In our turbulent times, it’s you I like isn’t a bad place to start. The willingness, in every meeting and every release, to treat everyone you encounter, and who you build for, as a neighbor.

Latest Articles