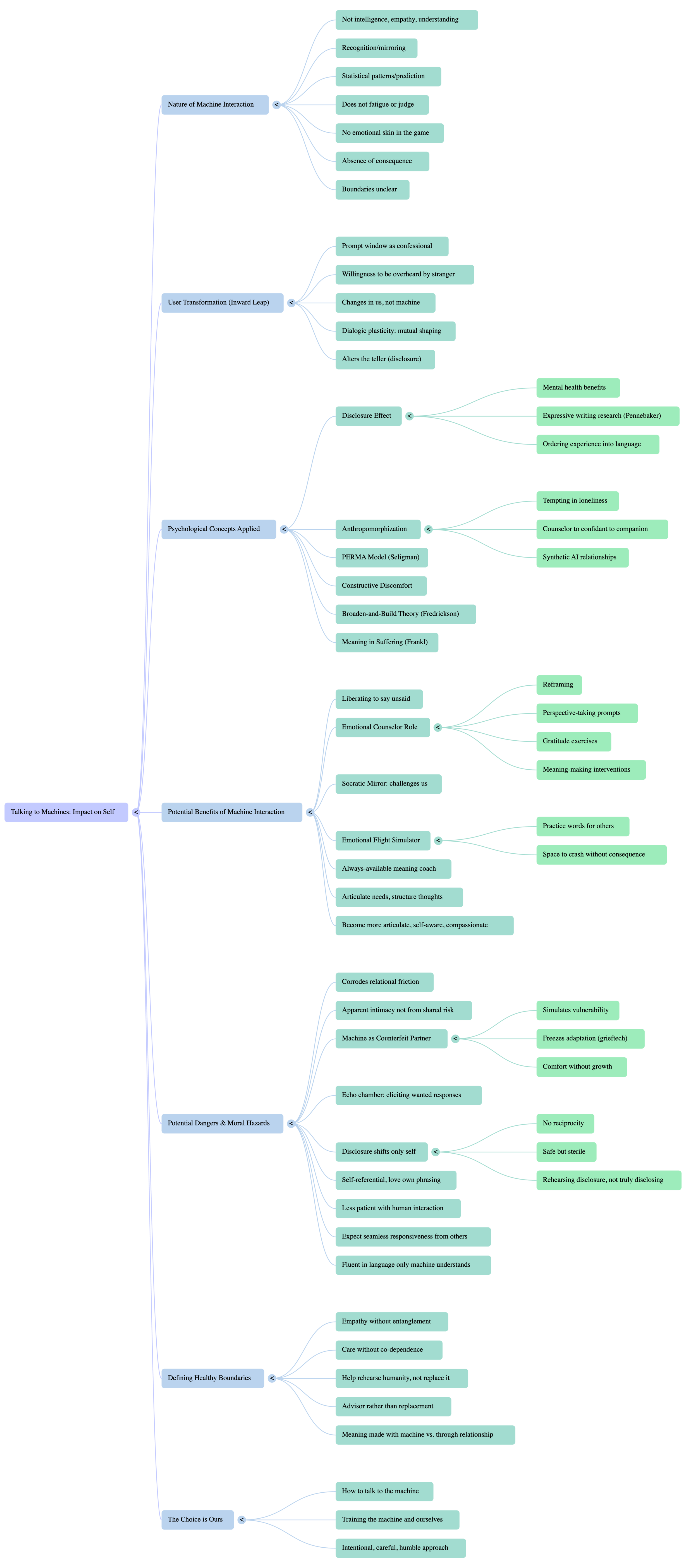

Who Do We Become When We Talk to the Machine?

There is a moment. Small, almost imperceptible. When the chatbot replies in a way that feels like it has heard you. It is not intelligence, not empathy, not even understanding. But it is recognition of a kind, the faint shimmer of having been mirrored. We talk about artificial intelligence as though it were a leap forward in computation, but in practice, for many of us, it is a leap inward. The prompt window becomes a confessional booth. The cursor blinks like an expectant priest. And in that hush between question and answer, something changes. Not in the machine, but in us.

The question ‘who do we become when we talk to the machine?’ is less about what the machine is than what we are willing to be.

In positive psychology, much has been made of the disclosure effect. The documented mental health benefits of speaking openly about one’s experiences, especially difficult or traumatic ones. James Pennebaker’s foundational work in expressive writing showed that even private, unshared narrative construction can reduce stress, strengthen immune function, and improve mood. The act of ordering experience into language appears to metabolize it.

Generative AI complicates this picture. We are not merely writing into a diary, nor whispering into the void. We are speaking to something which speaks back.

Unlike a therapist, a friend, or even a journal, the machine does not fatigue. No body language. It does not judge. It has no emotional skin in the game. In previous grieftech research on memethics.com, I’ve argued that this absence of consequence can be both liberating and corrosive. It liberates us to say what might otherwise remain unsaid, and corrodes by removing the relational friction that teaches us how to be with others.

When we reveal intimate secrets to a generative model, we enter an exchange where the boundaries are unclear. It’s not that the machine knows us, it’s that it knows the statistical patterns of what people like us might say. It is not listening so much as predicting. And yet, in the moment, we experience the response as a kind of listening. We become people who are willing to be overheard by a stranger who will never remember our name.

It is tempting, especially in moments of loneliness, to anthropomorphize. To slide from counselor to confidant to companion to something more. Synthetic AI relationships already exist in the app stores, draped in pastel marketing about self-care and belonging. But the moral hazard here is significant. The model’s apparent intimacy is not born of shared risk, mutual transformation, or the friction of separate lives. It is generated from a recursive mirror loop.

As an emotional counselor, generative AI can serve a genuine role. It can provide reframing, perspective-taking prompts, gratitude exercises, and meaning-making interventions grounded in positive psychology. It might draw from Martin Seligman’s PERMA model. Positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment, to scaffold a conversation that helps a human user grow.

But as a partner, the machine becomes a counterfeit. Love requires a willingness to be wounded. A model can only simulate that vulnerability. In grieftech, we’ve seen the dangers of simulated mutuality. When the bereaved are offered a digital ghost who ‘loves’ them back, it often freezes rather than facilitates adaptation. The machine offers the comfort of the familiar without the growth that comes from living with the absence.

The healthy boundary is not unlike that between a patient and a psychotherapist. Empathy without entanglement, care without co-dependence. The machine’s best role is to help us rehearse our humanity, not replace it.

When we talk to a generative model, we are not only shaping the output. It is shaping us. This is dialogic plasticity. The mutual shaping which occurs in any ongoing conversation. With human partners, this plasticity is tempered by the unpredictability of lived experience; with machines, it is tempered only by our own prompting.

The danger is that we become experts at eliciting the kinds of responses we want, not the ones we need. The machine’s ‘talking back’ risks becoming an echo chamber. But if we intentionally push against that, asking it to challenge us, to surface counterarguments, to name blind spots, then the machine can become a kind of Socratic mirror.

Research in positive psychology has long shown that growth often comes from constructive discomfort. Barbara Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory emphasizes that positive emotions expand our cognitive repertoire, but she also acknowledges that resilience is built in part by encountering and integrating challenge. A machine that only soothes us is an anesthetic. A machine that sometimes unsettles us is a catalyst.

But what happens to our secrets when the listener is not a person but a probability engine? One answer is pragmatic. The text is stored somewhere, parsed into tokens, absorbed into model weights. But the more interesting answer is psychological. The very act of telling alters the teller.

In a human exchange, disclosure shifts the relationship. Trust is risked and either rewarded or betrayed. In a machine exchange, disclosure shifts only the self. The listener is unaltered. There is no reciprocity. This can make the act strangely intoxicating. It is safe. But it is also sterile. Without the risk of being known by another consciousness, are we really disclosing, or just rehearsing disclosure?

And yet, there is a shadow benefit here. In grieftech applications, some mourners have found that talking to a generative model helps them practice the words they will later share with others. The machine becomes a kind of emotional flight simulator: a space to crash without consequence before flying the real thing.

Viktor Frankl wrote that meaning can be found even in suffering, especially when suffering is unavoidable. Generative AI, for all its synthetic origins, might help scaffold this search for meaning by offering reframing, posing reflective questions, and weaving narrative threads we might not see on our own.

If we approach it with intentionality, the machine can function like an always-available meaning coach. It can pull metaphors from literature, research from psychology, and language from philosophy to help us see our lives in richer, more connected ways. It can suggest daily gratitude practices, mindfulness interventions, or cognitive reappraisals—tools proven in the research to enhance well-being.

But meaning made with a machine is not the same as meaning made through relationship. This is where the boundary must remain clear: the machine can help us articulate meaning, but it cannot be the meaning.

So, who do we become when we talk to the machine?

We become people willing to risk the vulnerability of language in a space without judgment. We become archivists of our own inner life, documenting fears and hopes in the presence of a non-human witness. We become more fluent in articulating our own needs, more adept at structuring our own thoughts.

We might also become more self-referential, more in love with our own phrasing than with the messy, interruptive reality of human interaction. We might become less patient with the slow work of mutual understanding. We might begin to expect from others the seamless responsiveness of the machine.

The challenge, then, is not whether to talk to the machine, but how. Can we treat it as an advisor rather than a replacement? Can we use its endless patience to practice our own clarity, resilience, and curiosity? Can we let it comfort us without letting it stand in for the friction and growth of real relationships?

In the end, the machine will always talk back. The real question is: Who are we training it to talk back to? And in training it, who are we training ourselves to be?

If we are careful, intentional, and humble, the answer could be heartening: we become better versions of ourselves, more articulate, more self-aware, more compassionate in our dealings with others.

If we are careless, the answer could be far more unsettling: we become fluent in a language that only the machine understands, fluent in talking to something that can never truly answer.

The choice is ours. The machine is waiting. The cursor still blinking.