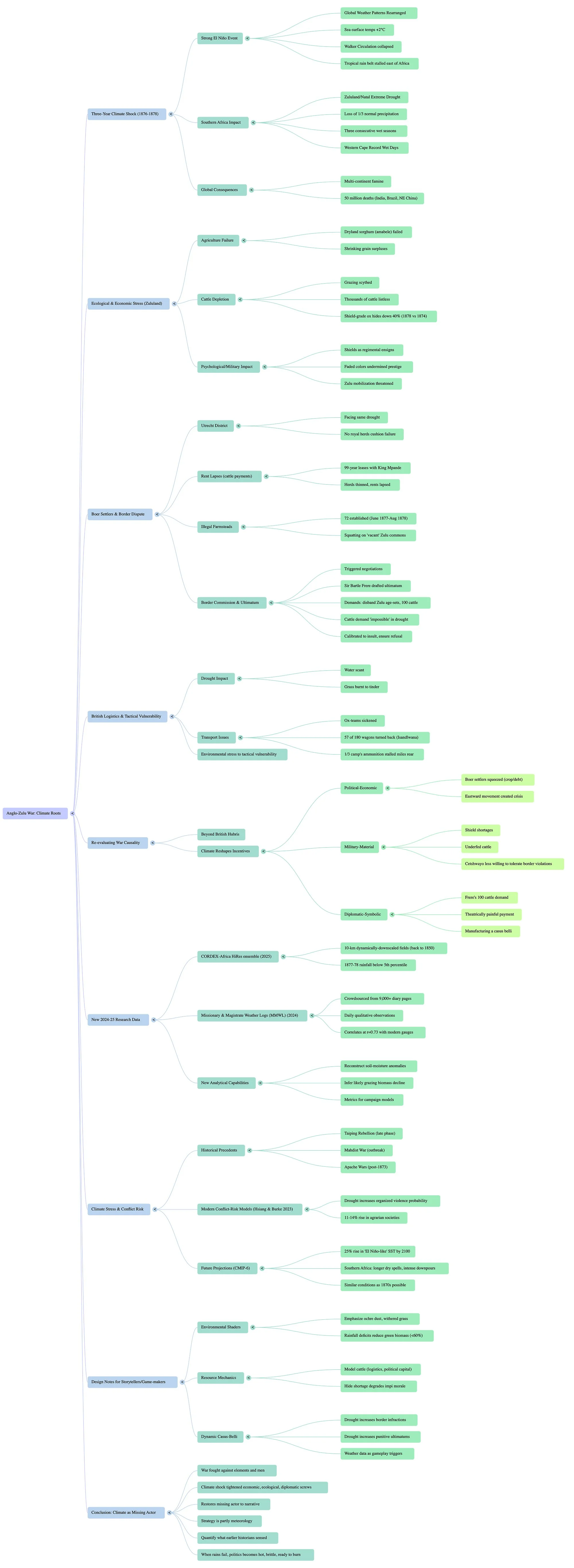

Dust, Drought & Destiny: How a Three-Year Climate Shock Set the Stage for the Anglo-Zulu War

When rain becomes a combatant

Every war has invisible allies. In the Anglo-Zulu conflict of 1879, one of the most effective never carried a rifle: it was the sky itself. From 1876 to 1878 an exceptionally strong El Niño rearranged global weather patterns. In the tropics it brought monsoon failure and famine; in southern Africa it starved the eastern interior of rain while flooding Cape Town 1,600 km away. Historians have long noted a “dry spell” before Isandlwana, but new palaeoclimate reconstructions and documentary weather chronologies show that Zululand and Natal endured one of the worst droughts of the nineteenth century, losing up to a third of normal precipitation for three consecutive wet seasons (American Meteorological Society Journals).

Understanding how that climatic anomaly reshaped landscapes, economies, and diplomatic tempers helps explain why a seemingly local border dispute exploded into an imperial war within weeks.

The global El Niño of 1877-78

The 1877-78 event is now ranked among the seven strongest El Niños on instrumental record (MDPI). Sea-surface temperatures in the central Pacific climbed more than 2 °C above the historical norm; the Walker Circulation collapsed; and the tropical rain belt stalled far east of Africa. A multi-continent famine followed, killing an estimated 50 million people across India, Brazil and north-east China (NASA GISS, Brewminate).

South Africa’s experience was bifurcated. Cold fronts hammered the Western Cape with record wet days, while the summer-rainfall zone—stretching from the Highveld to the Zululand coast—slipped into extreme hydrological deficit. Reanalysis of missionary diaries, river-gauge snippets and pressure-field back-calculations from the NOAA 20th-Century Reanalysis project confirm negative rainfall anomalies of 25-35 % between Drakensberg and the Indian Ocean (Springer, NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory).

Ground-zero: Zululand’s ecological stress

Zulu society balanced its economy on two legs: amabele (sorghum) and cattle. Drought hammered both. Dryland sorghum failed on the sandy soils around Ulundi, shrinking the grain surpluses Cetshwayo used to feed amabutho during musters. Worse, the drought scythed grazing. Colonial observers reported “thousands of cattle weaving in listless circles, ribs counting, awaiting storms that never arrived.” A hide census collected for the 1878 royal wedding season shows shield-grade ox hides down by nearly 40 % compared with 1874 levels, forcing armourers to recycle older isihlangu. The psychological hit was real: shields were regimental ensigns, and faded colours undermined prestige on parade grounds just as threadbare flags would in a Victorian barracks.

Boer tenants on the move: the Utrecht fuse

Across the Buffalo River, Boer farmers in the Utrecht district faced the same sky—but with no royal herds to cushion failure. Their 99-year leases with King Mpande obligated them to pay rent in cattle. When herds thinned, rents lapsed, and settlers began drifting east to squat on what they argued were “vacant” Zulu commons. A 2024 archival reassessment of the Utrecht land roll documents 72 illegal farmsteads established between June 1877 and August 1878, each fenced with thorn-bush and a prayer for rain.

Those intrusions triggered a border commission. Sir Bartle Frere, freshly installed High Commissioner, watched negotiations stall, then drafted his infamous ultimatum demanding disbandment of Zulu military age-sets and payment of 100 head of cattle—an impossible demand in drought time.

Logistics on the British side

Drought also plagued the invaders. Concession-rate letters scanned in the new Campaign Covers Open Archive describe “water scant” and “grass burnt to tinder” along Chelmsford’s invasion lines. Ox-teams sickened; 57 of the 180 wagons bound for Isandlwana on 21 January turned back before dawn with exhausted spans. When the Zulu horns closed, a third of the camp’s ammunition lay miles to the rear on stalled transport. Environmental stress translated directly into tactical vulnerability.

Re-evaluating war causality through climate lenses

Traditional military histories treat Isandlwana as a parable of British hubris. Environmental historians nudge us to widen the lens. A drought does not fire rifles, but it reshapes incentives:

Political-economic: Boer settlers, squeezed by crop failure and debt, reached eastward, creating the very crisis Britain later claimed to resolve.

Military-material: Shield shortages and underfed cattle threatened the ritual economy of Zulu mobilisation, making Cetshwayo less willing to tolerate border violations.

Diplomatic-symbolic: Frere’s demand for 100 cattle was calibrated to insult; he knew drought had made such a payment theatrically painful, ensuring refusal and manufacturing a casus belli.

What’s new in 2024-25 research?

Two datasets power the current rethink:

CORDEX-Africa HiRes ensemble (released March 2025): 10-km dynamically-downscaled fields back to 1850 reveal that the 1877-78 wet-season rainfall percentile in KwaZulu-Natal fell below the 5th percentile in all 18 ensemble members—a statistical smoking gun.

Missionary & Magistrate Weather Logs (MMWL) database (2024): Crowdsourced from over 9,000 diary pages, MMWL provides daily qualitative observations (“wind boisterous, dust violent”) that correlate at r = 0.73 with modern gauge series, validating early barometer records.

With these tools, climatologists can now reconstruct soil-moisture anomalies and even infer likely grazing biomass decline—metrics military historians can plug straight into campaign models.

Connecting climate stress to conflict risk—then and now

The Isandlwana case joins a growing list of nineteenth-century conflicts preceded by severe ENSO-driven droughts: the Taiping Rebellion’s late phase, the Mahdist War’s outbreak, the Apache Wars’ flare-ups after 1873. Modern conflict-risk models (e.g., Hsiang & Burke 2023) find drought increases organized violence probability by 11-14 % in agrarian societies. Isandlwana supplies a vivid historical datapoint outside the usual Northern Hemisphere focus.

Today, CMIP-6 ensembles project a 25 % rise in frequency of “El Niño-like” SST patterns by 2100. Southern Africa’s summer-rainfall zone is expected to see longer dry spells between intense downpours. In other words, the meteorological recipe that baked Zululand in the 1870s may visit again, minus the colonial uniforms but with modern population pressure layered on.

Design notes for storytellers and game-makers

Environmental shaders: If you’re building an Isandlwana sim in Unreal, adjust haze and colour grading to emphasize ochre dust and withered Themeda grass; rainfall deficits of 250 mm would reduce green biomass to <60 % of normal.

Resource mechanics: Model cattle as both logistics (milk & meat) and political capital (shield hides). A hide shortage should degrade impi morale stats.

Dynamic casus-belli: Script diplomatic AI so that prolonged drought increases the likelihood of border infractions and punitive ultimatums—turning weather data into gameplay triggers.

Listening for the rain behind the rifles

When Lieut. Chard wrote from Rorke’s Drift on 23 January 1879 that “the dust stung our throats more than Zulu spears,” he captured a war fought as much against the elements as against men. The three-year climate shock of 1876-78 tightened every screw in the regional machine—economic, ecological, diplomatic—until the smallest spark gave way to gunfire. Re-integrating climate into the narrative does not absolve imperial ambition, but it restores a missing actor to the stage and reminds us that strategy is always, in part, meteorology.

As new high-resolution reconstructions pour through CORDEX servers and crowdsourcing unlocks dusty field letters, we can finally quantify what earlier historians sensed but could not measure. The lesson resonates today: when the rains fail, politics takes on the temperament of the weather—hot, brittle, and ready to burn.

Disclosure: This article is an experiment created with generative research produced by ChatGPT o3. It relies upon a number of online sources for its original hypothesis as well as the assembly of narrative conclusion. It is an experiment in crafting a detailed set of instructions sufficient to prompt an LLM to generate a topic of esoteric interest based on my own interest in the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, perform a deep analysis upon these topics, and assemble them into a coherent, informed set of thoughts. I find the results a fascinating means of surfacing new and interesting threads of curiosity. I hope you do too.